If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to get in your DeLorean or your Way-Back Machine and scoot back in time half a millennium or so to Tudor England, but aren’t sure you’d relish the lack of penicillin, unhealthy food preparation, and unsanitary waste management, you’ve got a chance right now to have an experience analogous to watching an original performance by Shakespeare’s own dramatic company without leaving the relative safety of the 21st century: Go see a Shakespeare performance at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London.

Today’s Globe is located on a plot of land in Southwark about 750 feet from the site of the original Globe theatre, built in 1599 on the south bank of the Thames by Richard Burbage, leader of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the acting troupe of which Shakespeare was a member and for which he wrote his plays. The original playhouse was built of timbers saved from Burbage’s father’s playhouse, The Theatre, which had just been demolished on the north side of the city. Henry V, Hamlet, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, King Lear, Othello, Antony and Cleopatra, and other classics were all performed there for the first time. The building was destroyed by fire in 1613, though by that time Shakespeare’s company (now the King’s Men) was ready to abandon it and were performing at Blackfriar’s indoor theater. But the original Globe had been a marvelous venue in good weather. It held some 3,000 spectators, the more well-healed of whom sat on tiered benches ranged in a gallery looking down at a thrust stage roofed with thatch, around which hundreds of less well-off spectators, the “groundlings,” stood looking up at the stage throughout the performance.

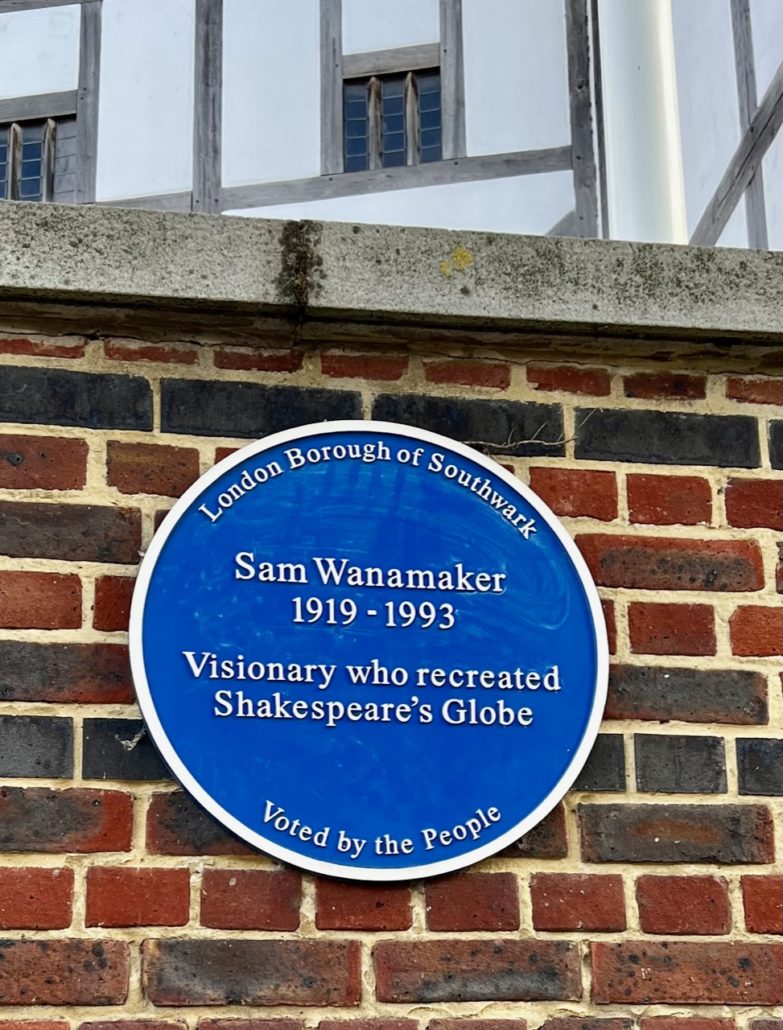

In 1970, the American actor and director Sam Wanamaker (known for films like The Spy Who Came In from the Cold and TV series like Holocaust), who had lived in England since the McCarthy-era blacklist in the United States, conceived the idea of creating a modern replica of the original playhouse, as authentic as possible, with an acting company that would perform a season of Shakespearean plays each summer. Wanamaker raised millions of dollars for his project, was not stymied by myriad roadblocks local authorities tried to put in his way, and finally was able to begin construction of the replica, with the current Elizabeth in support of a project that recalls the golden age of her namesake. The new Globe is modeled according to the best scholarly evidence of what Shakespeare’s Globe would have been like, even to the point of having the only thatched roof allowed in London since the Great Fire of 1666. For safety reasons, the modern theatre accommodates only 1400 spectators, several hundred of whom are modern “groundlings” who stand around the stage.

Unfortunately, having worked for 24 years on the project, Wanamaker died in 1994, three years before his dream finally became a reality and the new Globe was opened in 1997 by the Queen herself. Like its namesake, the new Globe opened with a production of Shakespeare’s Henry V, under founding artistic director (Tony and Oscar winner) Mark Rylance.

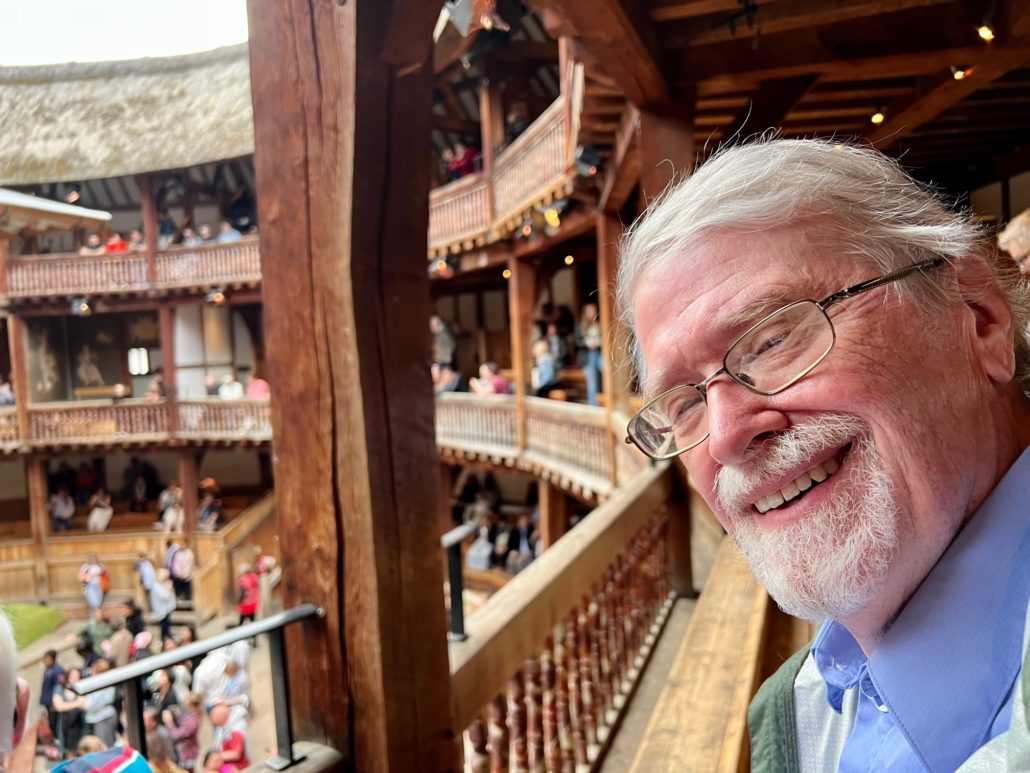

In London for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, there was no way this Rambling Writer was going to miss a chance to see a play at the new Globe, especially since it’s having its own Silver Anniversary this summer. There are a number of possibilities for shows, as this season includes King Lear, The Tempest, Julius Caesar, as well as the seldom performed Henry VIII, but I was glad to see that for the nights we were in London, the Globe was staging one of my favorite comedies: Much Ado About Nothing.

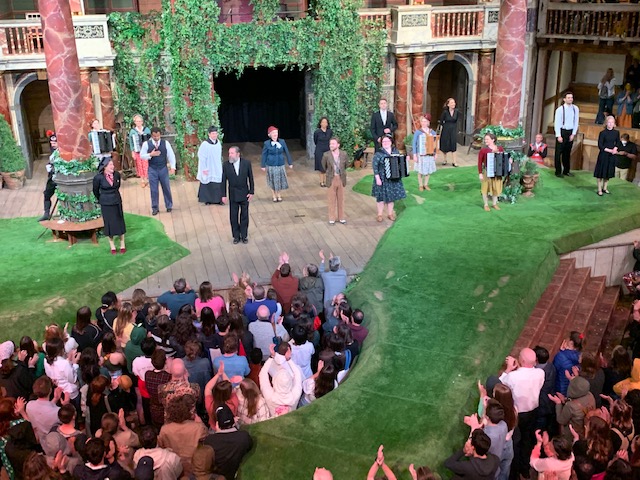

Venerable British theatre director Lucy Bailey has staged Much Ado as a kind of garden party (fitting for the “green world” comedies of the period of Shakespeare’s Much Ado, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night), and has taken the Italian setting of the original play and placed it in an Italy of 1945. Personally, I’ve never been a fan of the modern directors’ insistence on never setting Shakespeare’s plays in Elizabethan times. I never know just what kind of point they are trying to make with the time shifting and suspect it’s just a lot cheaper to use more modern dress than to create authentic looking Elizabethan-era costumes. Of course, Shakespeare himself dressed the characters in his Roman plays in contemporary English costumes, so such things have their precedents. In this case, though, I thought it worked well: As troops are returning from the war in Italy, a celebratory mood of peace-come-back-again pervades the play.

Another, more recent, trend in productions of the bard is the playing with and bending of gender. This, too, is prefigured by Shakespeare himself, whose women’s roles were always played by men. In this production, Bailey has cast the two old men Leonato and Antonio, respective fathers of the heroines Hero and Beatrice, as mothers instead: Leonata (Katy Stephens) and Antonia (Joanne Howarth) play the parts as women who are not about to be dominated by the likes of the Duke Don Pedro and his soldiers, especially Claudio and Benedick, whose arrival is a kind of male invasion of the peaceful feminine space of Leonata’s garden—ringed throughout the production by an all-female accordion band who add music and gaiety to almost every scene. One more thing casting Leonata as a woman does: It creates the opportunity of a romantic partner for the Duke himself.

Much Ado rises or falls with the chemistry between Beatrice and Benedick, whose dueling barbs and witticisms create much of the humor and whose eventual pairing, helped along by the machinations of their friends who trick them into loving each other—or perhaps in realizing their mutual attraction—rounds off the play. In this production, Ralph Davis as a rather awkward Benedick opposite Lucy Phelps’ sarcastic Beatrice have chemistry to spare, and in particular Phelps’ direct interaction with the groundlings builds in the audience a tremendous empathy for the characters, so there is a great felt elation when the two get together.

Something similar might be said of George Fouracres as the hapless magistrate Dogberry, who spends a good deal of time weaving his way through the groundlings and even ends up evoking sympathy with his chagrin at being called “ass” by the penitent villain Boracio.

This is a brilliant, sparkling, glorious production to open the Globe’s 25th season. If you are in London, it’s a treat any time to come to a production at the Globe. You want to feel the immediacy and the universality of Shakespeare? Go and see him performed at the place that brings you closer to the original performance than anyplace else. Tickets are probably cheaper than you’d pay at the West End or at Broadway—seats in the galleries range from 35 to 70 pounds, but you can be a groundling for 5 pounds, and it looked to me like that could be a lot of fun. (You may want to rent seat pads for a couple of bob from the provider inside the venue when you get there if the hard bench seems daunting to you). Check out the Globe’s web site if you want to see some Shakespeare this summer: https://www.shakespearesglobe.com