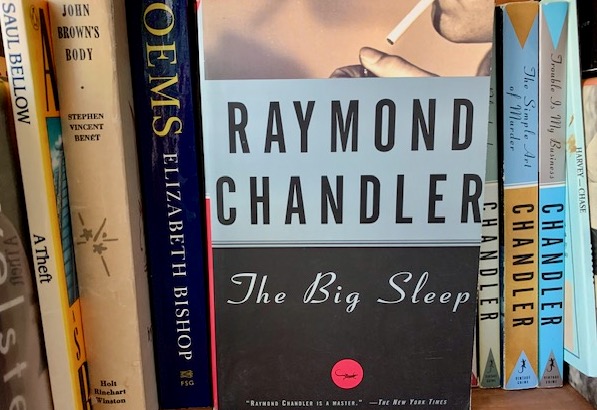

Order Tramadol 50 mg Dorothy Sayers, a crime novelist herself, famously wrote that the detective story “does not, and by hypothesis never can, attain the loftiest level of literary achievement.” Thus the “hard-boiled’ detective fiction of Raymond Chandler and his peers like Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain whose novels inspired the film noir of 1940s American cinema, was traditionally considered less “legitimate” than “literary” fiction. But it has been much better appreciated in recent decades, so that novels like Chandler’s The Big Sleep, featuring his signature tough-guy private eye Philip Marlowe, are far more likely these days to appear on “best novel” kinds of lists. As Chandler wrote, in response to Sayers’ assertion, “It is always a matter of who writes the stuff, and what he has in him to write it with.” While some of his other novels, particularly The Long Goodbye and Farewell My Lovely, have their adherents, Chandler’s first novel, 1939’s The Big Sleep, has enjoyed the most popularity—likely enhanced by Howard Hawks’ classic noir film featuring Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe. It was the first pairing of Bogart and Lauren Bacall, and featured a screenplay co-written by no less a figure than William Faulkner. What’s not to like?

https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/Purchase tramadol without prescription No one since that film’s release in 1946 has ever been able to read the book without imagining Bogart as Marlowe. The novel was included on Time magazine’s 2005 list of the 100 best novels since 1923. It also appeared on both the Guardian’s and the Observer’s top 100 novels lists, and in 1999 was voted number 96 on the French newspaper La Monde’s list of the 100 Books of the Century, comprising novels from throughout the world. And it comes in at number 18 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Philip Marlowe is in many ways the quintessential hard-boiled private eye, with an imperturbable surface cool, an unflappable cynicism about the human race, and a determination to get to the bottom of any mystery. But he’s not simply a tough-guy stereotype, as compared to, say Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, who is essentially just that, a hammer in a world where everything looks like a nail. Beneath his outer shell, in contrast, Marlowe has human feelings and a moral compass, and will not take a job for any money if he doesn’t feel it’s right. Marlowe, born, as Chandler tells us, in Santa Rosa, California, had a few years of college and worked for a while as an insurance investigator before joining the office of the district attorney of Los Angeles county. When the DA’s office fired him for insubordination, Marlowe became a private investigator.

The plot of the novel is complex and filled with shady characters who might double cross you at any point. It opens with Marlowe being called to the home of General Sternwood, a rich old gentleman who has two daughters. The elder, Vivian, has an absentee husband named Rusty Regan, who hasn’t been seen for some time. The younger, a “wild” young thing named Carmen, who was once blackmailed by a man named Joe Brody, is actually being blackmailed again by a bookseller called Arthur Geiger, and the general wants Marlowe to deal with the current blackmailer. As Marlowe’s leaving the house, though, Vivian stops him to ask if her father hired him to find her lost husband, but he refuses to tell her.

After an investigation of Geiger’s book store, Marlowe discovers the store is a front for the distribution of illegal pornography. When Geiger leaves the store, Marlowe trails him home and remains to watch the house, observing his young blackmail victim enter. Hearing a scream and gunshots from in the house, then two cars speeding away, Marlowe enters the house to find Geiger dead on the floor and a drugged and nude Carmen tied to a chair before a camera. His client’s interests in mind, he first takes Carmen home, but returns to the house, only to find that Geiger’s body has disappeared. Marlowe does the same, but the next day he receives a call from the police, telling him that General Sternwood’s car has been discovered driven off a pier, with the murdered chauffeur dead inside. And the police, like the older daughter, also want to know if he is looking for the mysterious Rusty Regan.

That’s enough to let you know something of the twisting plot of the story, but I’m not going to give you any spoilers. But I think it is important to note that for Chandler, the intricate “plot as puzzle” story of the traditional detective genre was not its most significant element. In a famous Atlantic essay in December of 1944, he criticized traditional British mysteries (like those of Dorothy Sayers) because they failed to present events or characters or language that felt like the real world that people lived in. Their characters, he said, “must very soon do unreal things in order to form the artificial pattern required by the plot. When they did unreal things, they ceased to be real themselves. They became puppets and cardboard lovers and papier-mâché villains and detectives of exquisite and impossible gentility. The only kind of writer who could be happy with these properties was the one who did not know what reality was.”

In contrast Chandler praised his contemporary fellow American novelist Dashiell Hammett. Hammett’s style Chandler compared to Hemingway’s—simple and real. And Hammett, he added, “gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare, and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for these purposes.”

In praising Hammett, Chandler was of course speaking of himself as well, having a style honed, like Hammett’s, in the pulp magazines of the 1930s. Like Chandler himself, Hammett “was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.” Thus for Chandler, realism was important, in details of the plot and the setting. Language is important. Characters are important, every one of which should be drawn from the real life of the world in which murders take place. And of most importance is the reality of the detective himself. In the climax of his essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” Chandler waxes profound:

“The realist in murder writes of a world in which gangsters can rule nations and almost rule cities, … It is not a fragrant world, but it is the world you live in.” But “In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption. It may be pure tragedy, if it is high tragedy, and it may be pity and irony, and it may be the raucous laughter of the strong man. But down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor — by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.”

Such a world is the world of The Big Sleep. And such a man is Sam Spade. These were the things that Chandler wrote about and what he cared about in his writing. As for the elaborate plots, they were secondary. So it was that, while filming The Big Sleep, director Howard Hawkes contacted Chandler and told him he couldn’t figure out who exactly had killed General Sternwood’s chauffer. Chandler replied, honestly, that he didn’t know either.

Read the book yourself. Maybe you can figure it out. Then watch the movie. You’re guaranteed to like it.