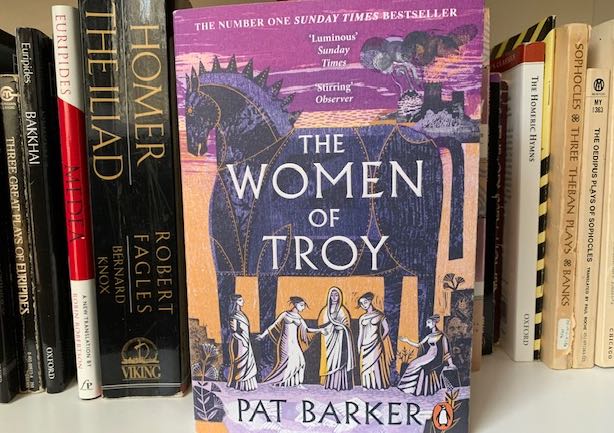

Order Tramadol 100Mg Online https://www.petwantsclt.com/petwants-charlotte-ingredients/ The Women of Troy

Pat Barker (2021)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

If you can’t quite place the name Briseis, you can probably be excused. It’s not Hecuba or Hellen. It’s not Cassandra or Penelope. Briseis is simply a very minor character in The Iliad—albeit a significant one, since she is, according to Homer, the cause of the rift between Achilles and Agamemnon. A beautiful princess given to Achilles as his war prize, she is taken away by Agamemnon when that commander of Greek forces is compelled to give up his own war prize, the girl Criseis, daughter of a priest. In Pat Barker’s novel The Women of Troy, Briseis’s viewpoint becomes central to our understanding of the sorrows, the dreams, and the compulsions that motivate the enslaved women of that fallen city as the Greek army prepares to dissolve and to return, each warrior to his own home. Briseis herself, pregnant with Achilles’ child, had been given to his lieutenant Alcimus when Achilles was slain and so, unlike the rest of the women in the book, she is not a slave and can circulate freely among the various warriors’ households.

Barker’s source for this novel is not the epic poet Homer but rather the tragic poet Euripides, whose drama The Women of Troy provides Barker’s title. Barker uses the details of Euripides’ play as a framework for her novel’s plot: The Greeks are beset with winds that will not allow them to leave Troy as punishment for allowing Ajax the Lesser to rape Hecuba and Priam’s daughter Cassandra after dragging her away from a statue of the goddess Athena. Hecuba, widow of King Priam and former queen of Troy, is given as a slave to Odysseus, author of Troy’s destruction through the strategy of the Wooden Horse. Cassandra herself is given as concubine to the Greek general Agamemnon, though the prophetess Casandra knows she is going to her death when Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra will kill him and Cassandra herself when they arrive in Argos. Andromache, widow of the Trojan hero Hector, is broken when their young son Astyanax is thrown from the battlements of Troy to ensure that he will never grow up to avenge his father’s death. The body of the boy is brought to his mother, carried on Hector’s own shield. And Hecuba’s youngest daughter, Polyxena, is slain as a human sacrifice on the tomb of Achilles. Meanwhile the woman whose infidelity was the root cause of the war, Helen, though officially condemned to death, is apparently reconciled with her husband Menelaus and destined to live happily with him in Sparta.

But Barker’s novel does merely retell Euripedes’ story. Euripedes, whose best-known works tend to focus on female protagonists, like Medea, Electra, Phaedra, and of course the Trojan Women, is a convenient starting point for Barker’s plan of retelling the story of the Trojan war from the perspective of the women who tend to have little or no agency in the original texts. As such, Barker’s work is part of a popular recent trend among women writers, one that has its roots perhaps as far back as Nobel laureate Louise Glück’s collection The Triumph of Achilles, but received significant impetus from Margaret Atwood’s 2006 novel The Penelopiad—the Odyssey retold from Penelope’s point of view. More recent contributions have been Meadoe Hora’s Ariadne’s Crown (2019), Madeline Miller’s Circe (2020), Claire Heywood’s Daughters of Sparta (2021), Jennifer Saint’s Ariadne (2021), Natalie Haynes’ The Children of Jocasta (2017) and A Thousand Ships (2021), Hannah Lynn’s Grecian Women trilogy (2021-22), and of course Barker’s own The Silence of the Girls (2018), the prequel to The Women of Troy, which I had no idea existed until reading the current book. Surely this is a significant current phenomenon, through which women are reclaiming the female perspective in the myths, especially as related by Homer, that shaped the beginnings of western culture.

In The Women of Troy, Barker goes beyond Euripedes by adding not only the narrator Briseis, but several other significant characters, the most important of which is Pyrrhus, son of Achilles, whose character Barker explores in chapters alternating with Briseis’s first-person sections. At the beginning of the novel Pyrrhus is waiting in paralyzing insecurity with the other Greek soldiers in the belly of the wooden horse. When released he charges forth and enters the chamber of Priam, king of Troy, whom he slaughters so clumsily that the dying king taunts him: “Achilles’ son?” he says. “You? You’re nothing like him.” Through the rest of the book, the insecure teenager keeps trying awkwardly to live up to his heritage. He spends much of his time polishing his father’s great shield. The rest of the time he spends dragging the corpse of Priam around behind his chariot, as Achilles had dragged Hector. When he finally leaves off that occupation, he leaves the body to rot, forbidding anyone from burying it.

As a result, much of the plot owes a great deal to another celebrated female figure from Greek mythology, Sophocles’ Antigone. Barker creates a character named Amina, who had been in the room with Hecuba when Pyrrhus killed Priam, and who, in violation of Pyrrhus’s order, yearns to bury her fallen king, despite Briseis’s cautionary pleading to the contrary. The enraged Pyrrhus vows to find whoever dared violate his order, and Briseis’s husband Alcimus argues that there are only two Trojans in the camp: Priam’s youngest son Helenus (who betrayed his father under torture) and the priest Calchas, who fled to the Greeks early in the war in the belief that Troy was doomed to fall. The blindness of this reasoning—the failure to consider that there are literally dozens of Trojans in the women’s quarters—underscores the chief themes of the book: the brutality of men, and women as chattel, especially in a time of war. When Pyrrhus discovers a woman has dared to disobey him—particularly one who saw his awkward insecurity in the murder of Priam—he reacts predictably. Men are afraid women will laugh at them; women are afraid men will kill them, to paraphrase an assertion attributed to Margaret Atwood. This is the male brutality that, in our earliest literature, is glorified and immortalized, to the detriment of women and their civilizing role. With apologies to Euripedes, the complete story of the women of Troy, from their own perspectives, has had to wait until now.

Barker has been criticized for the anachronistic coarseness of some of her language, but it makes little sense, in a novel that seeks to revisit a heroic tale from the point of view of the raped and degraded, to frame that story in the exalted language of the epic itself. Thus there is no hallowed language in Barker’s book, just as there are no hallowed gods. “Guardian of cities? Is that a joke? “ Briseis says of Pallas Athena. “Let’s bloody hope she’s not guarding this city.”

If you’re looking for an uplifting summer read for the beach, this is probably not it. It’s a bleak tale that features the captive women who either, like Hecuba, cannot bring themselves to recognize their newly degraded position; or, like Amina, display a “joyless rectitude” that leads to her own destruction—or, like Briseis herself, pragmatically try to go on living in a world where she has neither value nor agency, except as a vessel for the next generation of patriarchal brutality. But it’s a thoughtful, timely book and an impressive achievement by one of Britain’s finest contemporary authors.