They Shall Not Grow Old

Peter Jackson (2018)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

These are the third and fourth stanzas of the 1914 poem “For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon, well-known throughout the British Commonwealth for its use in the “Ode of Remembrance,” traditionally recited on “Remembrance Day” (November 11) commemorating the end of what was called the Great War. Binyon wrote the poem after the British suffered heavy losses in the battle of the Marne on the Western Front early in the war, not knowing how much greater would be the losses on that front over the next four years. The Ode is recited at extended ceremonies at the Menin Gate in Ypres after buglers have sounded the “Last Call,” honoring the 300,000 British and Commonwealth troops who died in the trench warfare there in Flanders Fields. It is the first line of the poem’s fourth stanza, the most familiar part of the “Ode of Remembrance,” that provides the title of Peter Jackson’s new documentary about British infantry soldiers in the trenches of World War I’s Western Front.

They Shall Not Grow Old is the Oscar-winning director’s first foray into the territory of the documentary—at least as a director (Jackson did produce West of Memphis, the 2012 documentary on the West Memphis Three). The BBC, in concert with the Imperial War Museums and the UK government arts program “14-18 NOW,” contacted Jackson in 2015, commissioning him to make a film using the 100 hours of archival film footage from the war held in the Imperial Museum, in addition to the 600 hours of interviews with 200 veterans of the Great War, recorded by the BBC and the IWM in the 1960s and ’70s, while those veterans were still available. The only requirement was for Jackson to use the materials in a unique and creative manner. I urge you to see the film, now showing at Riverdale 10 and at Colonel Glenn, and you’ll see that Jackson has certainly fulfilled his end of the bargain.

What you see in the beginning of the film is some of the original black-and-white footage, unrestored (or at least not completely restored), depicting the recruitment and training of troops at the beginning of the war and their shipping out for France and, with the arrival on the continent, there is a Wizard of Oz moment when the picture expands to fill the wide screen, and everything turns to color. The soldiers, as Jackson says, would have seen battle in color, and what he has tried to do in the film is recreate for audiences, as closely as modern technology may allow, what it was really like being a combat soldier in the trenches during the Great War. Film that had faded nearly to white, or decayed nearly to black, has been cleaned up and the image sharpened. Frame rates of the old films have been adjusted to contemporary standards, so the movements of the figures are all natural, as if they had been filmed yesterday. It is as if these long dead soldiers have suddenly come to life, in the glory of their youth and the pathos of their impending doom.

Color has been added thoughtfully and carefully, the technicians studying the colors of British and German uniforms, and the colors of the landscapes of Flanders Fields, so that colors in the film are as realistic as possible. Jackson has employed forensic lip-readers, so that when any figures are seen to be speaking in the film footage, a voice—with the correct regional accent—is synced with his lip movements so that the words spoken more than a hundred years ago are recaptured and become part of the film. Other sound effects—exploding shells, firing guns, squeaking rats—are reproduced as realistically as possible, using World War I era guns. Music from the First World War forms a subtle and barely noticeable background to some moments of the film, and a male chorus sings a rowdy version the popular and cynical war song “Mademoiselle from Armentières” over the credits. This last song, which Jackson had decided to use as he was finishing production on the film, is sung by a hastily assembled group of British government employees in New Zealand, since Jackson wanted to make sure to have genuine British voices, rather than New Zealanders, ending the film.

Then there are the voice-overs. After listening to those six hundred hours of recorded interviews, Jackson and his crew made the decision not to impose any modern voices of scholars, historians, or Great War enthusiasts in the film, but rather to allow only the soldiers themselves, who had taken part in action on the Western Front, to speak over the images. There are dozens of these voices, never identified in the actual film but listed by name and by affiliation in the ending credits. The comments, coupled with corresponding images, are arranged in a kind of chronology, beginning with memories of how the men came to enlist (we learn how many of them were too young, perhaps 16 or 17, but lied about their ages in order to join up), then moving on to their basic training, their arrival on the continent, and then their experiences in the trenches—the camaraderie among the troops, the miseries of lice and of rats, the horrors as well as the excitement of actual combat, the terrors of tanks and gas warfare, relationships with German prisoners, the numbness felt at the ceasefire, and the difficulties of resuming any normal life on their return home.

Jackson makes no political statement in the film, makes no attempt to analyze the war’s meaning or results from a historical perspective. He does not try to give a sweeping presentation of all aspects of the war, ignoring the eastern front, the war at sea and the introduction of airplanes in combat, or the war on the home front and the role of women in factories. He admits all of this (and describes how he made the film) in a half-hour commentary that follows the film in the theaters that you can stay to watch. He decided early on that the film would focus only on the experience of trench warfare, that aspect of the war that has become synonymous with our impressions of World War I over the years. And this the film captures to an uncanny extent. You have literally never seen anything like it.

The film premiered last October 16 in Great Britain at the London Film Festival and in selected theaters, and was broadcast on BBC Two on the centennial of the Armistice that ended the war on November 11. It had a very limited U.S. release through Fathom Events on December 17 and 27, then was released in New York and Los Angeles on January 11, and finally in 25 other markets in February. It was nominated for a BAFTA Award as Best Documentary, but missed the filing deadline to be eligible for an Oscar nomination—and cannot be nominated for 2019 either, since it was released in 2018. This is a shame, because it is a monumental achievement.

It turns out the title is not simply an allusion to the patriotic “Ode of Remembrance.” It is also a statement that has become literally true: The young men filmed in these century-old images have been restored to their youth through the magic of Jackson’s technology. This is remarkably poignant with a group of Lancashire fusiliers, grouped before moving into battle in one section of the film. Jackson tells us in the commentary following the film that this group of men was almost completely wiped out in the subsequent attack—we are seeing them in the last 30 minutes of their lives. But as the title says, they have not grown old: Jackson has succeeded, in a sense, in resurrecting them from the dead. This is a miracle that you need to see for yourself. Four Shakespeares for this one.

NOW AVAILABLE!!!

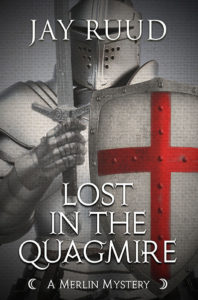

Jay Ruud’s most recent novel, Lost in the Quagmire: The Quest of the Grail, IS NOW available from the publisher AS OF OCTOBER 15. You can order your copy direct from the publisher (Encircle Press) at http://encirclepub.com/product/lost-in-the-quagmire/You can also order an electronic version from Smashwords at https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/814922

When Sir Galahad arrives in Camelot to fulfill his destiny, the presence of Lancelot’s illegitimate son disturbs Queen Guinevere. But the young knight’s vision of the Holy Grail at Pentecost inspires the entire fellowship of the Round Table to rush off in quest of Christendom’s most holy relic. But as the quest gets under way, Sir Gawain and Sir Ywain are both seriously wounded, and Sir Safer and Sir Ironside are killed by a mysterious White Knight, who claims to impose rules upon the quest. And this is just the beginning. When knight after knight turns up dead or gravely wounded, sometimes at the hands of their fellow knights, Gildas and Merlin begin to suspect some sinister force behind the Grail madness, bent on nothing less than the destruction of Arthur and his table. They begin their own quest: to find the conspirator or conspirators behind the deaths of Arthur’s good knights. Is it the king’s enigmatic sister Morgan la Fay? Could it be Arthur’s own bastard Sir Mordred, hoping to seize the throne for himself? Or is it some darker, older grievance against the king that cries out for vengeance? Before Merlin and Gildas are through, they are destined to lose a number of close comrades, and Gildas finds himself finally forced to prove his worth as a potential knight, facing down an armed and mounted enemy with nothing less than the lives of Merlin and his master Sir Gareth at stake.

Order from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Quagmire-Quest-Merlin-Mystery/dp/1948338122

Order from Barnes and Noble here: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/lost-in-the-quagmire-jay-ruud/1128692499?ean=9781948338127