If Beale Street Could Talk

Barry Jenkins (2018)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

You might remember Barry Jenkins’ last film, a little thing called Moonlight, which garnered eight Academy Award nominations and took home three Oscars, including Best Picture. That film, which had been based on an unproduced semi-autobiographical drama by playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, told the story of a young black man trying to find himself in a hostile world. The movie, telling a compassionate but troubling story, was a surprise winner over the uplifting but far less substantive La La Land.

So it’s no great surprise that Jenkins’ new film, If Beale Street Could Talk, is not exactly the feel-good movie of the season either. Adapted from acclaimed author James Baldwin’s 1974 novel of the same name (the title comes from a line in the old W.C. Handy standard, “Beale Street Blues”), the film is thematically rather close to Moonlight: It tells the story of a young black couple in early 1970s New York, struggling to find a place for themselves in a world that seems hostile to their love, in a country designed to keep them from succeeding.

The first scene of the film shows us the couple, 19-year-old Tish Rivers (KiKi Layne in her first movie role), and 22-year-old Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (Stephan James of Selma), attractively dressed in autumnal colors as they stroll casually through a park under yellow leaves and look lovingly into one another’s eyes. This idyllic scene is undercut with the next shot, which shows Tish visiting Fonny in prison, speaking to him on a phone with a barrier of glass between them. She is there to tell him that she is pregnant with his child. After the initial shock, Fonny is overjoyed with the idea, though he wishes (it matters more to him than to her, Tish as narrator tells us) that they could be married. They agree that the ceremony should take place as soon as he is cleared of the false charges that have put him here, and he is free once again. Fonny does want to know if she has told her family or his father (a curious specification which becomes more understandable before long), but Tish says she wanted to tell Fonny first.

The next two scenes provide a stark contrast between Tish’s family and Fonny’s. When Tish reveals her condition to her parents and her sister, there is a pregnant pause (no pun intended) until her father Joe (Colman Domingo, also from Selma) overcomes his shock and decides the news is worth celebrating. Mother Sharon (Regina King from TV’s American Crime, who has already won a Golden Globe for this performance) was on board from the beginning, as was Tish’s feisty sister Ernestine (Teyonah Parris of TVs Empireand Mad Men). The scene is almost unparalleled in American cinema—spontaneous and unprecedented support for an unmarried 19-year old mother-to-be. But a whole different note is struck when the family invites Fonny’s parents over to share the news and celebrate with them. Fonny’s mother (Aunjanue Ellis from TheHelp), an overbearing holier-than-thou Evangelical Christian demands to know who is going to take care of the child, tells Tish that “I always knew you’d be the destruction of my son,” and ultimately actually calls on God to curse mother and baby. Fonny’s sisters, cookie-cutter versions of their Mom, are in full support, while his father Frank (Michael Beach of TV’s ERand Third Watch), overjoyed at the news, brings the party to a screeching halt by battering his overbearing wife.

The two scenes underscore two of Baldwin’s (if not Jenkins’) favorite themes: In his later works (like BealeStreet), Baldwin emphasized the importance of the family as a cornerstone of African American culture and identity, and Tish’s loving bulwark of a family demonstrates that theme. As for Evangelical Christianity, it should be noted that Baldwin, in his late teens, was himself an Evangelical preacher, and a very popular one, but grew to see that form of religion as a sham, and ultimately rejected religion altogether, declaring that Christianity had reinforced the institution of slavery by depicting temporal trials as God’s will and promising some kind of salvation in the sweet by-and-by. He would later write, in The Fire Next Time, that “If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him.” Clearly God has not made Mrs. Hunt any larger, freer, or more loving. The implication is, its time to get rid of her concept of God.

The story of the film progresses in scenes of flashback—showing us Tish and Fonny’s deepening relationship, his growth as a woodworking artist, and their difficulties in finding a suitable place to live in Greenwich Village as landlord after landlord refuses to rent to a young African-American couple; alternating with scenes in the present, with Tish visiting an increasingly disillusioned Fonny in jail while her family, particularly her mother Sharon, tries to find evidence to prove Fonny innocent of the rape charge for which he is incarcerated awaiting trial.

It is clear from the beginning that Fonny cannot possibly be guilty of the crime, having a sound alibi and having been on the other side of the city when the crime took place. But he’s been tagged for the crime by a corrupt and vengeful police officer (a smarmy Ed Skrein of Deadpool), and in a racist legal system, it’s his innocence that must be proven, not his guilt. Officer Bell’s foil is the other significant white character in the film, the defense attorney Hayward (Finn Wittrock of TV’s The Assassination of Gianni Versace), whose well-meaning ineffectiveness is helpless against a system designed to protect the likes of the vile Officer Bell. The fact that, ultimately, the film is able to generate a sense of hope amid this distorted system is a product of Jenkins’—and Baldwin’s—portrayal of the close and supportive family sustaining the young couple through adversity.

The effect of the film is achieved not so much through the gentle, subdued action and soothing music in the scenes between Tish and Fonny, but particularly through the more dynamic energy of the supporting characters, as in the scene with Fonny’s mother. Another particularly seering scene is Fonny’s conversation with his old friend Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry of TV’s Atlanta), just out of prison on a marijuana charge he pled guilty to in order to avoid a false charge of stealing a car, of which he was accused even though he doesn’t know how to drive. Daniel’s pained account of his abuse in prison, where “they can do with you whatever they want,” is hard to ignore: “The white man has got to be the devil,” Daniel says, with the unsilenced voice of the powerless, “because he sure ain’t a man.”

Most memorable of all is probably Sharon, who works tirelessly to obtain Fonny’s release, even flying to Puerto Rico, where the prosecution has spirited away the rape victim Victoria Rogers (Emily Rios of TV’s From Dusk Till Dawn) to keep their case from being blown. The meeting between Sharon and Victoria is devastating and crushing, the fragile Victoria’s psyche as crushed by the legal system as Tish’s promises to be, and Sharon’s disappointment as raw as Fonny’s with the stark denial of justice.

This film is likely to leave a lasting effect on you, and it’s certain that the issues it raises are still with us, 45 years after the novel’s original publication. One need look no further than the difficulty the NFL is having finding acts willing to perform during halftime of the upcoming Super Bowl, after their official stance regarding Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling support of the “Black Lives Matter” movement. It’s certainly one of the best films of 2018. Four Shakespeares for this one.

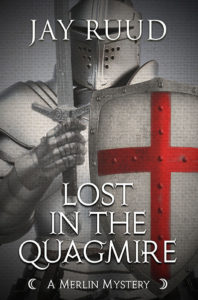

NOW AVAILABLE!!!

Jay Ruud’s most recent novel, Lost in the Quagmire: The Quest of the Grail, IS NOW available from the publisher AS OF OCTOBER 15. You can order your copy direct from the publisher (Encircle Press) at http://encirclepub.com/product/lost-in-the-quagmire/You can also order an electronic version from Smashwords at https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/814922

When Sir Galahad arrives in Camelot to fulfill his destiny, the presence of Lancelot’s illegitimate son disturbs Queen Guinevere. But the young knight’s vision of the Holy Grail at Pentecost inspires the entire fellowship of the Round Table to rush off in quest of Christendom’s most holy relic. But as the quest gets under way, Sir Gawain and Sir Ywain are both seriously wounded, and Sir Safer and Sir Ironside are killed by a mysterious White Knight, who claims to impose rules upon the quest. And this is just the beginning. When knight after knight turns up dead or gravely wounded, sometimes at the hands of their fellow knights, Gildas and Merlin begin to suspect some sinister force behind the Grail madness, bent on nothing less than the destruction of Arthur and his table. They begin their own quest: to find the conspirator or conspirators behind the deaths of Arthur’s good knights. Is it the king’s enigmatic sister Morgan la Fay? Could it be Arthur’s own bastard Sir Mordred, hoping to seize the throne for himself? Or is it some darker, older grievance against the king that cries out for vengeance? Before Merlin and Gildas are through, they are destined to lose a number of close comrades, and Gildas finds himself finally forced to prove his worth as a potential knight, facing down an armed and mounted enemy with nothing less than the lives of Merlin and his master Sir Gareth at stake.

Order from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Quagmire-Quest-Merlin-Mystery/dp/1948338122

Order from Barnes and Noble here: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/lost-in-the-quagmire-jay-ruud/1128692499?ean=9781948338127