Mimi Leder (2018)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/SusannTennyson.jpg’ attachment=313′ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

This new biopic about superstar Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is just out in wide release this week. Like many serious biopics filmed since Tony Kushner’s screenplay for Spielberg’s Purchase tramadol without prescription Lincoln, this one, penned by newcomer Daniel Stiepleman, focuses on a single major turning point in the subject’s life, rather than attempting to deal with all of Justice Ginsburg’s eighty-something years in a couple of hours on the screen. The film does spend some time with Ginsburg at Harvard Law School and in her fruitless job search before landing a professorship at Rutgers Law, before it settles in to tell the story of RBG’s first major case before the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1972—a case involving discrimination against a man, which provided the impetus to topple myriad other laws that discriminated on the basis of gender.

Stiepleman happens to be Justice Ginsburg’s own nephew, and reportedly Ginsburg exercised a good deal of control over the film, including providing notes on the script as well as approval of the film’s two leading actors—British actress Felicity Jones ( https://oleoalmanzora.com/oleoturismo-en-pulpi/ Rogue One, and Oscar nominated for The Theory of Everything), who plays Ginsburg herself, and Armie Hammer (Call Me by Your Name) as her almost-too-good-to-be-true husband Marty. The actors are interesting choices—the diminutive Jones actually looks a bit like the diminutive Ginsburg—but they tend to be somewhat two-dimensional in a film that borders on hagiography. Perhaps director Mimi Leder (The Peacemaker, Deep Impact) is handicapped by a reverence for the film’s subject to the extent that the film can only be formulaic, but in a sense the clichéd approach does a disservice to the complexity of this most significant justice of the past quarter century.

The tone of the film is set quite early, as we see Ruth walking through the Harvard campus, the only female face in a sea of masculinity as the song “Ten Thousand Men of Harvard” plays in the background. She is one of nine women in a class of 500 as she begins law school in 1956. At a dinner for the new ladies, hosted by the dean of the Law School, Erwin Griswold (the venerable Sam Waterston, whose Law and Order background makes him a natural for the role), Griswold asks each of the nine women present to justify herself: Why is she at Harvard Law School, taking up a spot that should have been filled by a man?

Ruth navigates the dangerous waters of misogyny and discrimination, buoyed somewhat by Marty, a year ahead of her in school and with whom she already has a daughter. When Marty is burdened by cancer in his last year, Ruth carries the weight for them both, continuing her studies but attending all of his classes as well. She helps him graduate, then moves to New York and finishes her degree at Columbia when he gets a job as a tax attorney. Unable to get a position in a New York firm despite graduating at the top of her class and making the Law Review at both Harvard and Columbia, Ruth is disgruntled to be teaching at Rutgers instead of practicing law. But it is Marty who finds the perfect case for her to litigate: It is Moritz v. Commissioner of the IRS, a 1972 case in which an unmarried Colorado man named Charles Moritz (a sympathetic Christian Mulkey of TV’s Liberty Crossing and Saving Grace), was disallowed a $296 tax deduction for hiring a nurse to help him care for his elderly mother. The law defined only women (or men whose wives were deceased or otherwise unable to provide care themselves) as caregivers, and so precluded Moritz from filing the claim. Marty puts the idea in Ruth’s head that if she can get the patriarchal court to rule that this law discriminates against men on the basis of sex, then the door is open to do the same with myriad laws on the books that discriminate in the same way against women.

Now this is the point at which the movie turns into a familiar outsider vs. the system, little-guy vs. the power structure, Cinderella team vs. the world champions story. When Ruth goes to see legendary feminist attorney Dorothy Kenyon (Kathy Bates), and is told to give it up, she’ll never beat the system, it’s like Barbara Hershey telling Gene Hackman not to try to recruit Jimmy for the Hoosiers team. When ACLU legal director Mel Wulf (Justin Theroux of The Last Jedi) scoffs at Ruth’s agenda but then agrees to add the ACLU’s name to the appeal of the Moritz case, it’s like Mick telling Rocky he needs to “fight this guy hard, like you done before!” And when Ruth falters in her big Meaningful Courtroom Speech but finds her confidence just in the nick of time, it’s like Roy Hobbs, down two strikes, blasting that last-second home run to lift the Knights to the pennant. Sure, you want to cheer at the end. Everything is designed to make that happen—even to the point of having Justice Ginsburg herself appear briefly in a kind of flash-forward on the steps of the Supreme Court in the closing moments of the film.

Sorry if some of this sounds like a spoiler, but it is, after all, history, and as predictable as it is possible to be. Justice Ginsberg has been quoted as saying that everything in the film is factually true—except that faltering in the presentation before the 10thCircuit Court of Appeals. That never happened. But it makes a more suspenseful movie, so why not throw it in? Roy Hobbs’ homer would have been less exciting in the 8th inning with a two-ball-no-strike count. But it still would have won the game.

The formulaic aspect of the script is one flaw in the movie. Another is the depiction of some of the men in the film, especially the opposing legal team in the trial, which appropriately includes Dean Griswold as well as another of Ruth’s former mentors, Professor Brown (Stephen Root of Office Space), both of whom are little better than caricatures, comfortably lodged in their intact patriarchy and horrified at the prospect of the destruction of the American family they are certain women’s equality will produce. One of the great strengths of the film is how the relationship between Ruth and Marty, based on a mutual respect and acceptance of ungendered roles in their marriage—Marty cooks! He does the dishes! He takes care of children!—is the basis of a sound, loving, and happy family, and produces an independent, intelligent and spirited daughter, Jane (Cailee Spaeny of Bad Times at the El Royale), who comes across as more lively than her humorless mother and her unfazable father.

In the end, the film is a solid lesson in how a determined Ginsburg took on a hundred years of bias in American law and started a revolution. But it is formulaic, and it’s also stiff and slow. There are times you feel compelled to try to pull the responses from the characters’ hesitating lips. I remember one of my own old directors who I am certain would have been sitting in the house, as he did in rehearsals, snapping his fingers and shouting “Pace! Pace!”

Go and see On the Basis of Sex if you want to—it may spark your interest and inspire you to learn more about Justice Ginsburg. But if you really want to see a film that reviews her life and career in a comprehensive, entertaining, and non-Hollywoodized manner, take a look at Julie Cohen and Betsy West’s outstanding documentary RBG, which came out earlier in 2018, and which really should be Oscar material. As for On the Basis of Sex, two Jacqueline Susanns and half a Tennyson for this one.

Order Tramadol Overnight Shipping NOW AVAILABLE!!!

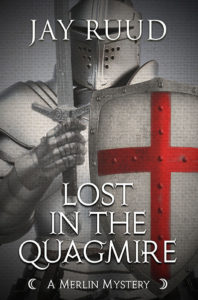

Jay Ruud’s most recent novel, Lost in the Quagmire: The Quest of the Grail, IS NOW available from the publisher AS OF OCTOBER 15. You can order your copy direct from the publisher (Encircle Press) at http://encirclepub.com/product/lost-in-the-quagmire/You can also order an electronic version from Smashwords at https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/814922

When Sir Galahad arrives in Camelot to fulfill his destiny, the presence of Lancelot’s illegitimate son disturbs Queen Guinevere. But the young knight’s vision of the Holy Grail at Pentecost inspires the entire fellowship of the Round Table to rush off in quest of Christendom’s most holy relic. But as the quest gets under way, Sir Gawain and Sir Ywain are both seriously wounded, and Sir Safer and Sir Ironside are killed by a mysterious White Knight, who claims to impose rules upon the quest. And this is just the beginning. When knight after knight turns up dead or gravely wounded, sometimes at the hands of their fellow knights, Gildas and Merlin begin to suspect some sinister force behind the Grail madness, bent on nothing less than the destruction of Arthur and his table. They begin their own quest: to find the conspirator or conspirators behind the deaths of Arthur’s good knights. Is it the king’s enigmatic sister Morgan la Fay? Could it be Arthur’s own bastard Sir Mordred, hoping to seize the throne for himself? Or is it some darker, older grievance against the king that cries out for vengeance? Before Merlin and Gildas are through, they are destined to lose a number of close comrades, and Gildas finds himself finally forced to prove his worth as a potential knight, facing down an armed and mounted enemy with nothing less than the lives of Merlin and his master Sir Gareth at stake.

Order from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Quagmire-Quest-Merlin-Mystery/dp/1948338122

https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/Buy Cheap Tramadol Overnight Order from Barnes and Noble here: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/lost-in-the-quagmire-jay-ruud/1128692499?ean=9781948338127